Hailed as one of the greatest stained glass artists of all time, Harry Clarke contributed in establishing Ireland’s unique artistic voice during the early years of the Free State.

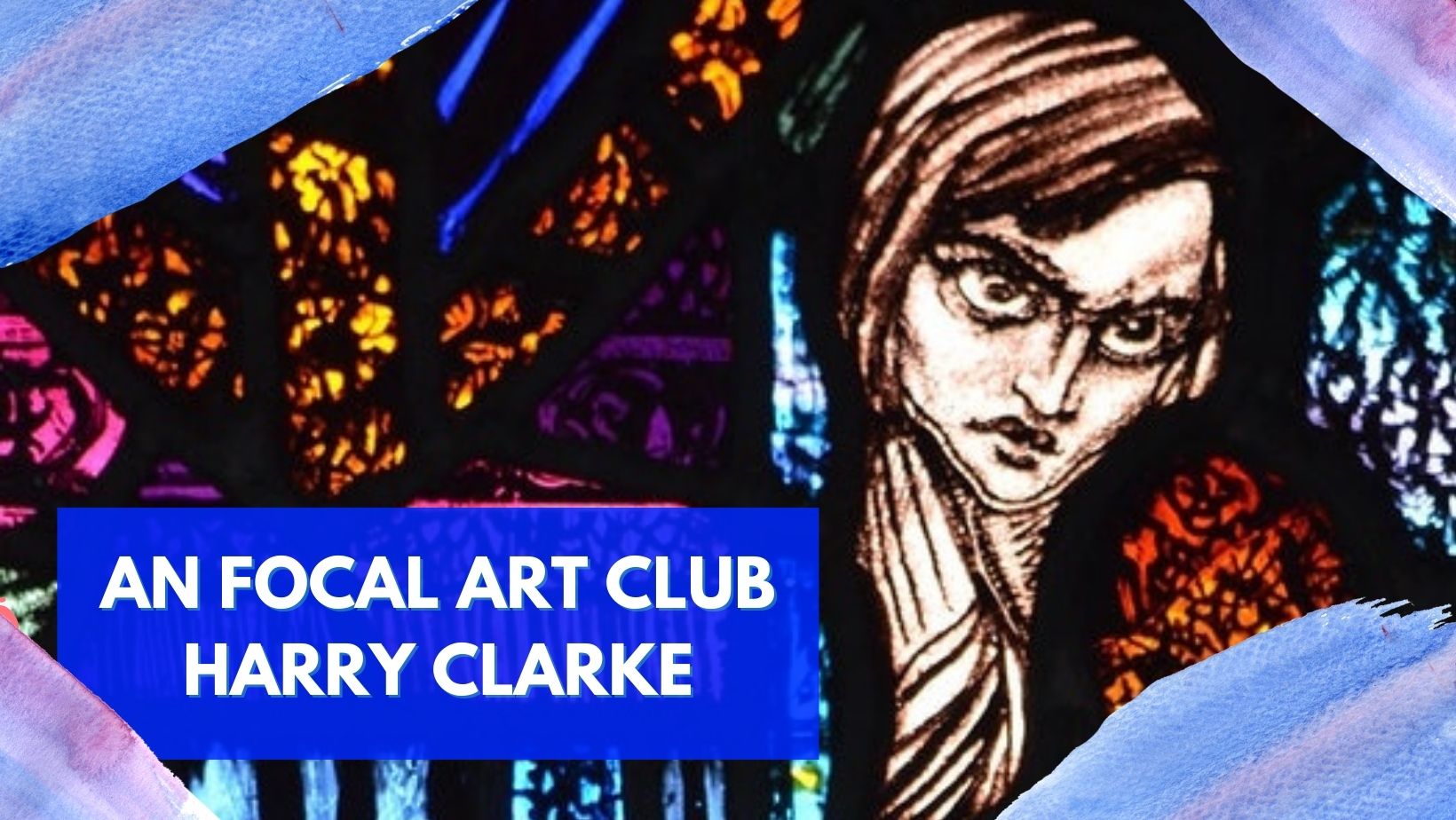

With vivid lively faces rooted in the revival of Gothic stained glass imagery, Harry Clarke is remembered as one of Ireland’s greatest artists and mastered both drawing and glass in his short, prolific life.

As leading figure in illustration and the Irish Arts and Craft movement, his work is dotted throughout the country and his illustrations are a bookshelf favourite, depicting stories from writers such as Edgar Allen Poe and Hans Christian Andersen.

With his short, meteoric career defined by producing multiple masterpieces in both the medium of stained glass and illustration, the Dublin born genius was inspired by the major Irish political and social changes at the time while also being deeply informed in literature and European art.

His career coincided with the early days of the Irish Free State and his distinctive, lively figurative drawing etched him into history as a major Irish talent with an independent and brilliant identity.

Despite his colossal talents, he was also shunned by the government for his depictions of his country’s literature and died feeling rejected by the authorities after they dismissed his masterpiece, The Geneva Window.

His large body of work is celebrated today and defined by explosive, rich colour and masterful grotesque figurative drawing.

Harry Clarke was born on 17th March 1889. His father was a church decorator originally from Leeds who moved to Dublin in 1887. He ran a decorating business named Joshua Clarke and Son that later expanded included stained glass in its trade.

A young Clarke battled with poor health for his life and this was worsened by the strong chemicals used in his craft of stained glass.

His mother, Brigid MacGongal died when he was only fourteen and this gravely affected him, with his work often exploring mortality and ageing.

After attending Belvedere college, Clarke started as an apprentice in his father’s studio before he enrolled in the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art to study stained glass.

A brilliant student, he won a gold medal from the Board of Education National Competition for his depiction of the Consecration of St Mel.

He married artist Margaret Crilly, a native of Co. Down and had three children, Michael, David and Ann.

One of his first commissions was from a Nationalist MP, Laurence Waldron who became a patron and a firm friend of Clarke’s.

In 1913, Clarke moved to London and secured his first illustration commission to depict the Fairytales of Hans Christian Andersen that was published in 1916 and received widespread acclaim.

His timing was perfect as his venture as an illustrator coincided with the golden age of gift book illustration and his work led him standing alongside masters such as Arthur Rackham and Virginia Frances Sterrett.

He moved away from working solely for his father’s studios and began taking his own commissions, such as nine windows for the Honan Chapel in Cork.

After his father’s death in 1921, Clarke moved to his studios in North Frederick Street and managed the stained glass department while his brother Walter took care of the decorating.

He continued to make his renowned reputation by taking his own commissions which garnered global acclaim such as his Ascension Window in Brisbane’s St Stephen’s Cathedral that still draw hordes of tourists in the present day.

He risked his reputation after he was commissioned to design a window for the International Labour Court in Geneva. Inspired by Ireland’s literary greats Joyce and O’Flaherty, the window was never exhibited.

It was bought back by his wife Margret and now is ion permanent exhibition at the University of Florida, Miami. It is now considered a masterpiece.

Alongside crafting windows in both the UK and Ireland, Clarke also continued to illustrate books such as The Year’s at the Spring.

In 1929, Harry was diagnosed with TB furthered propelled by the stress he was under completing his first American commission for the Basilica of St Vincent De Paul in New Jersey. Forced to leave the project incomplete, he left to travel to Switzerland for rehabilitation.

While Clarke was in Switzerland, his brother Walter continued to manage Joshua Clarke and Sons, however he died suddenly in 1930 leading to Clarke returning to Dublin facing a huge backlog of work.

He completed the Geneva window in October 1930 and exhibited it in his studios.

Despite efforts to contact the Irish government on their decision about this work, they never responded.

While Clarke always wished to die at home in Dublin, he died in Switzerland in his sleep at the age of 41, leaving a legacy behind of being one of the greatest stained glass craftsmen of the 20th century.

As one of the leading figures of the Irish Arts and Crafts movement, Clarke produced religious stained class work and they can be characterised by his distinctive treatment of faces with large, expressive eyes and influences of Celtic, Christian and Pagan imagery.

This is where a young Clarke learned various art styles, but was most inspired by Art Nouveau, an international style of art inspired by natural forms such as the curves in plants and flowers. There is also a asymmetry and the use of modern materials such as iron, ceramics and glass.

Clarke’s excellence at Stained glass windows informed his drawing, with his use of deep colours unusual for the time and inspired by Gothic cathedral in Charters.

In illustration, he used heavy black lines in his illustrations derived from glass techniques.

Clarke created over one hundred stained glass windows in his short but prolific career and his illustration of Edgar Allen Poe’s Tales of Mystery and Imagination brought him widespread acclaim of in the United States and made his style recognisable to a global audience.

Clarkes career coincided with the establishment of the Free State. As Ireland had no history of indigenous stained glass work and his work, heavily inspired by medieval art, brought a wider European influence to his commissions.

Inspired by playful gothic grotesque add intrigue to his art style.

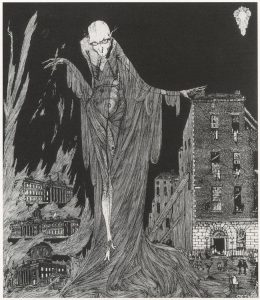

He was renowned for bringing back the medieval glass tradition, with grotesque humour steeped in morbid connotations appealing to Clarke, particularly in his later years when he knew his TB was fatal.

Critics have cited Clarke’s lifelong bad health as a great inspiration to his practice, with the apocalypse and death often featuring in his works.

Witnessing the turbulence of Ireland’s struggle for independence also inspired Clarke, with the violent conflict of the Civil War and the urban decay and poverty in Dublin’s Georgian mansions near Clarke’s studios a source of inspiration for some of his illustrations.

Clarke was also passionate about photography, and used to set up models for different scenes in his windows with his brother Walter often posing for him.

Throughout his life, his work won three national competition for his stained glass panels.

He would often contain a subtle self portrait of himself in his works, with this example where he uses his own face as one of the plague victims with no eyes in St Gobinat.

This work depicts the conditions Clarke witnessed at nearby tenements in Dublin. Remnants of fire still burning after both the War of Independence and the Civil War feature in the background. A new figure emerging from the tenements, acting as a personification of postcolonial Ireland.

The Geneva Window (1929)

This work was originally commissioned by the Department of Industry and Commerce for the International Labour Court, with eight panels depicting 20th century Irish literary imagery. The writers whose work Clarke depicted were Padraig Pearse, Lady Gregory, G B Shaw, J M Synge, Seumas O’Sullivan, James Stephens, Seán O’Casey, Lennox Robinson, W B Yeats, Liam O’Flaherty, George AE Russell, Padraic Colum, George Fitzmaurice, Seamus O’Kelly and James Joyce.

W.B Yeats was immensely excited about the project, however the depiction of Nelly and a drunken Gilhooley led to WT Cosgrave’s conservative views getting in the way of the commission ever being honoured by the new Irish State.

Clarke travelled to Switzerland to recover from his poor health after receiving a letter from Cosgrave condemning the piece and he died without ever having received a reply.

It is now held in Wolfsonian Foundation in Miami, Florida and is celebrated as one of Clarke’s greatest works.

Chapel of the Sacred Heart, Dingle (1922)

Clarke produced these masterpieces when commissioned by Sister Ita Macken to install 12 stained glass windows for her convent chapel designed by JJ McCarthy in Green Street, Dingle. Famed for their rich colours and exquisite decoration, the lively faces still draw crowds in Kerry almost one hundred years after they were commissioned.

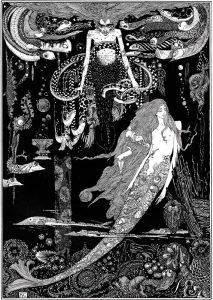

Illustrations for Hans Christian Andersen’s Fairy Tales(1916)

Clarke’s illustrations of Han’s Christian Andersen’s Fairy Tales were infamous and sold widely by Harrap’s of London. They are renowned for their intricate detail, expressive faces and masterful use of colour.

An Article:

“Into the light – An Irishman’s Diary on Harry Clarke” written by Noel Curren for The Irish Times.

http:/www.irishtimes.com/opinion/into-the-light-an-irishman-s-diary-on-harry-clarke-1.4449914

A Video:

“Harry Clarke – Is this Ireland’s Favourite Painting?” RTÉ 2012.